The Jurisprudential Basis for Kinship-Centred Disability Support: Aligning NDIS Funding with UNDRIP and International Human Rights Precedents

Uluru also known as Ayers Rock

Dr Jorandi (Jo) Kisiku Sa’quawei Paq’tism Joseph Randolph Bowers PhD

Executive Summary

The intersection of disability support and Indigenous rights in Australia represents a critical frontier in the pursuit of substantive equality and self-determination. Central to this discourse is the tension between the administrative protocols of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS)—specifically its restrictive stance on funding family members—and the collective rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as articulated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

The current NDIS framework is built upon a Western social and medical model of disability that prioritizes individual autonomy and market-based service delivery.1

However, for First Nations Australians, disability is often understood through a cultural lens where the individual’s well-being is inseparable from their connection to family, community, and Country.3

The National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) generally prohibits the payment of family members to provide supports, citing a perceived conflict of interest and an expectation that families will provide "informal support" as a matter of course.5

This report argues that this general rule constitutes a form of structural discrimination that fails to account for the unique kinship structures and historical traumas of Indigenous Australians. By drawing on UNDRIP, the National Agreement on Closing the Gap, and international precedents from New Zealand and Canada, a compelling case emerges for a broad and culturally informed exception to the conflict-of-interest rule. This exception is not merely a matter of administrative flexibility but a requirement for compliance with international human rights standards and domestic legal obligations.

The International Human Rights Imperative

UNDRIP and Collective Self-Determination

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2007 and endorsed by Australia in 2009, serves as the authoritative international framework for the protection of Indigenous rights.7

It establishes minimum standards for the survival, dignity, and well-being of Indigenous peoples globally, emphasizing both individual and collective rights.8

For Indigenous Australians with disability, UNDRIP provides a robust legal and moral foundation for demanding that disability supports reflect their cultural identity and social structures.

Articles 3 and 4: The Right to Self-Determination and Autonomy

At the heart of UNDRIP is the right to self-determination. Article 3 states that Indigenous peoples have the right to freely determine their political status and pursue their economic, social, and cultural development.7

In the context of the NDIS, self-determination remains hollow if participants are denied the right to choose the most culturally appropriate and safe person to provide their care.10 When the NDIA imposes an external provider on an Indigenous family, it effectively overrides the participant's right to determine the nature of their social and cultural development.

Article 4 extends this by affirming the right to autonomy or self-government in matters relating to internal and local affairs, as well as the "ways and means for financing their autonomous functions".7

This principle suggests that Indigenous communities should have a degree of control over how NDIS funds are allocated within their kinship networks. Financing an "autonomous function" can be interpreted as funding the existing community-led support systems that have sustained Indigenous people for millennia. The refusal to fund these systems while funding external, often non-Indigenous commercial entities, is a direct contradiction of the right to autonomy in financial and local affairs.3

Article 5: Maintenance of Social and Cultural Institutions

Article 5 upholds the right of Indigenous peoples to maintain and strengthen their "distinct political, legal, economic, social and cultural institutions".7

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, the extended family or kinship system is the primary social and legal institution. It is the mechanism through which lore is passed, care is managed, and social cohesion is maintained.1

The NDIS’s "informal support" policy—which expects these institutions to operate without financial recognition—undermines their economic viability. By categorizing kinship care as a "conflict of interest" to be avoided, the NDIA treats an essential Indigenous institution as a problem to be mitigated rather than a right to be protected.2

Article 24: The Right to Health and Traditional Practices

Article 24 of UNDRIP specifically addresses the right to health, stating that Indigenous peoples have the right to their traditional medicines and to maintain their "health practices".7

It also affirms that Indigenous individuals have an equal right to the "highest attainable standard of physical and mental health".7

For many First Nations people, the act of a family member providing care is a traditional health practice rooted in cultural concepts of reciprocity and communal responsibility.2

Cultural safety is an essential component of the "highest attainable standard" of health; without it, Indigenous participants frequently experience "double discrimination" and may withdraw from the scheme entirely to avoid traumatizing interactions with culturally incompetent external providers.1

Article 22: Special Needs of Persons with Disabilities

UNDRIP Article 22 explicitly demands that "particular attention shall be paid to the rights and special needs of indigenous elders, women, youth, children and persons with disabilities".7

This creates a positive obligation on the state to tailor its disability schemes to the specific needs of Indigenous people. A one-size-fits-all approach that ignores the primacy of kinship care fails this obligation by not providing the "full protection and guarantees" promised under the declaration.7

The Australian Context

The NDIS and the Conflict-of-Interest Doctrine

The National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013 was designed to promote the "independence and social and economic participation" of people with disability.15

However, the operationalization of these goals through the "choice and control" framework often results in a rigid adherence to Western market norms that do not align with Indigenous realities.

The General Rule and the "Informal Support" Expectation

The NDIA’s Operational Guidelines regarding "Sustaining Informal Supports" state that the agency will generally only fund family members to provide supports in "exceptional circumstances".5

The underlying logic is two-fold: first, that paying a family member may be "detrimental to family relationships," and second, that families have a natural obligation to provide unpaid support.6

It is argued that these gross and inappropriate assumptions are inherently colonial in bias and institutionally imbalanced in practice. The following table shows the structural and practical impact of these prejudicial policies on Indigenous Australian families.

Defining "Exceptional Circumstances"

The NDIA currently recognizes three broad categories of exceptional circumstances where family members may be paid:

1 Risk of Harm or Neglect: When the participant would be unsafe with an external provider.5

2 Religious or Cultural Reasons: When cultural norms dictate that only certain people can provide intimate or close care.20

3 Strong Personal Views: When the participant’s dignity or privacy is at stake.5

While these exceptions exist, they are often applied so narrowly that they become inaccessible to many First Nations participants. The burden of proof placed on a family to demonstrate that they are the only suitable provider is often insurmountable, particularly when the NDIA adopts a "deficit-focused model" that ignores the strengths of Indigenous kinship systems.17

Thin Markets and the Failure of Choice

The market-based model of the NDIS assumes that there is a pool of providers from which a participant can choose.

In many remote and regional areas, this market is non-existent.1

The Disability Royal Commission found that the lack of available, accessible, and culturally appropriate services for First Nations people is a "national crisis".24

In these "thin markets," the choice is not between a family member and a culturally safe external provider; it is between a family member and no support at all.3 Refusing to fund a family member in a region where no other provider exists is a failure to provide "reasonable and necessary" supports as required by Section 34 of the NDIS Act.19

International Precedents for Family-Based Funding Models

Comparative analysis of other Commonwealth nations reveals that Australia's restrictive approach is out of step with global trends toward Indigenous self-determination in social services.

The New Zealand Model: Whānau Ora and Funded Family Care

New Zealand’s Whānau Ora framework is a world-leading example of a culturally grounded, holistic approach to disability and health. It puts the whānau (extended family) at the centre of decision-making, acknowledging that individual well-being is dependent on collective health.25

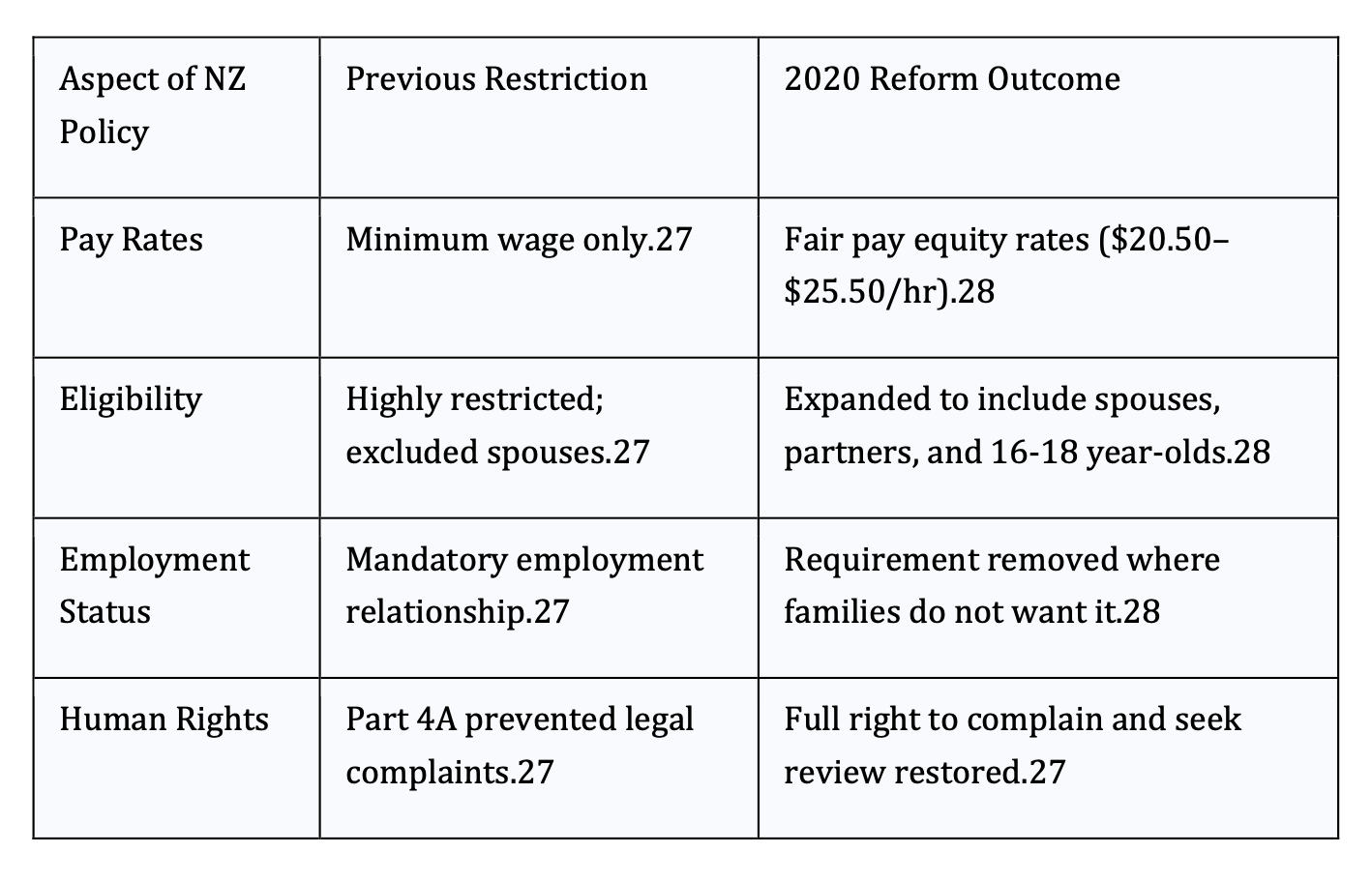

In 2020, the New Zealand government significantly reformed its "Funded Family Care" policy to address human rights concerns. Previously, New Zealand had legislation (Part 4A of the NZ Public Health and Disability Act) that limited the rights of families to challenge funding decisions.27 The repeal of this discriminatory law allowed for a more compassionate and rights-based approach. The table below highlights these reforms.

The New Zealand experience demonstrates that paying family members does not degrade the quality of care; rather, it "restores dignity" and recognizes the "important work family carers do".27 For Māori and Pacific families, who make greater use of these schemes, this policy is an essential tool for health equity.28

The Canadian Precedent: Jordan's Principle and Substantive Equality

In Canada, the legal framework for Indigenous disability care is driven by the principle of "substantive equality." This is most clearly seen in "Jordan's Principle," a child-first legal rule ensuring First Nations children can access all government-funded services without delays caused by jurisdictional disputes.29

Following a series of rulings by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, the federal government was found to have discriminated against First Nations children by narrowly defining essential services and underfunding Indigenous-led agencies.31 This led to a historic $23.34 billion settlement for families who were denied or delayed in receiving services.29

Furthermore, Canada's An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families (2020) affirms the "inherent right" of Indigenous peoples to exercise jurisdiction over their own child and family services.33

This provides a direct precedent for Indigenous Australians to argue that the NDIA must respect Indigenous-led designs of service delivery, including those that prioritize kinship care over external commercial providers.

National Policy Drivers

Closing the Gap and the Royal Commission

The Australian policy landscape is shifting toward a greater recognition of Indigenous sovereignty and the need for structural reform in disability services.

The National Agreement on Closing the Gap (2020)

The National Agreement on Closing the Gap is a pledge by all Australian governments to "do things differently" by working in genuine partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.35

The agreement is built around four "Priority Reforms" that directly challenge the current NDIS operating model.

Priority Reform 1: Shared Decision-Making: Governments must give Indigenous people a say in all decisions that affect them.35

This includes the design of individual NDIS plans and the choice of providers.

Priority Reform 2: Building the Community-Controlled Sector: Funding should be prioritized for organizations designed and controlled by Aboriginal people.35

A kinship-based funding model is the ultimate form of a "community-controlled" service.

Priority Reform 3: Transforming Government Organisations: Governments must address unconscious bias and systemic racism in their processes.35

The categorical dismissal of kinship care as a "conflict of interest" can be analysed as a systemic bias that devalues Indigenous social structures.

Findings of the Disability Royal Commission

The Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability (2023) highlighted that Indigenous people with disability are "culturally safe when people understand, respect and celebrate their First Nations identity".4

The Commission recommended that governments fund First Nations Community Controlled Organisations to provide "flexible supports and services".4

Crucially, the Commission acknowledged that "cultural safety, family, community, and connectedness are central to service delivery and engagement".40

This creates a powerful mandate for the NDIS to move away from the mainstream as well as "medical model" toward a "cultural model of inclusion".3

Legal Mechanisms for Advocacy

Human Rights Acts and the ART

Advocates in Australia have several domestic legal levers to challenge restrictive NDIA decisions regarding family funding.

The Queensland Human Rights Act 2019

The Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld) is a significant piece of legislation for Indigenous Australians. It protects fundamental human rights, including the "cultural rights of Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islander peoples".41

Section 28 of the Act specifically protects the right of Indigenous people to:

· Maintain and strengthen their distinct political, legal, economic, social, and cultural institutions.41

· Conserve and maintain their heritage and distinctive spiritual and cultural practices.42

Under Section 58 of the Act, "public entities" (which include registered NDIS providers and government departments) must act and make decisions in a way that is compatible with these human rights.43

An NDIS decision that refuses to fund a kinship-based support model could be seen as an unlawful limitation on the right of an Indigenous family to maintain their cultural institutions.42 While the NDIS is a federal scheme, the High Court and superior courts have increasingly recognized that state-based human rights obligations can influence the exercise of administrative discretion by federal delegates.41

The Administrative Review Tribunal (ART) and Merits Review

Participants who are dissatisfied with an NDIA internal review can appeal to the Administrative Review Tribunal (formerly the AAT). The Tribunal conducts a "merits review," meaning it steps into the shoes of the NDIA to make the "preferable decision".46

Advocates appearing before the Tribunal can argue that:

Cultural Necessity is an "Exceptional Circumstance": Drawing on the Operational Guidelines to prove that external care is inappropriate for the specific participant’s cultural needs.5

Market Failure and Reasonableness: Arguing that in the absence of other providers, funding a family member is the only "reasonable and necessary" way to achieve the goals in the participant's plan.4

Consistency with NDIS Objects: Arguing that Section 4 of the NDIS Act requires the role of families and carers to be "acknowledged and respected," which should extend to financial support in circumstances of economic hardship and service gaps.15

The Economic and Social Impact of Reform

The refusal to fund kinship care is not just a human rights issue; it is a failed economic policy that perpetuates intergenerational poverty.

Quantifying the Service Gap

Indigenous NDIS participants are 28% less likely to receive care than non-Indigenous participants.24

The "utilization gap" represents a significant failure in the NDIS’s promise of equity: it is the difference between the funding the government legally allocates to a participant and the amount that is actually spent on their care. Currently, First Nations participants utilize their funding at a rate of 72%, significantly lower than non-Indigenous participants .

This disparity is most acute in remote regions where "thin markets"—the total absence of external service providers—prevent participants from spending their budgets . We can calculate this systemic failure as a "Lost Benefit" ($B_{lost}$) to the community using the following model:

$$B_{lost} = F \times (1 - U_{util})$$

Where $F$ is the total funding allocated and $U_{util}$ is the utilization rate.

When the utilization rate ($U_{util}$) drops in remote areas, the "Lost Benefit" to the community is maximized.

By refusing to pay family members for care, the NDIA ensures this money remains unspent in government coffers rather than being used to support the participant. Reforming this rule would allow these funds to be "reclaimed" by the community. Instead of unspent potential, the funding would become a local salary, creating an economic multiplier that supports Indigenous employment and acts as a preventative safeguard against the types of family crises that lead to state-driven child removal .

Breaking the Cycle of Child Removal

A critical "third-order" insight is the relationship between NDIS funding and child protection.

In the Tennant Creek case, the withdrawal of NDIS funding for a boy with cerebral palsy led directly to his removal by the state.48

This highlights how rigid administrative rules can inadvertently contribute to "Closing the Gap" failures, particularly Target 12 (reducing the rate of children in out-of-home care).38

Funding kinship care is therefore a "safeguard" that promotes and protects an individual's right to live with their family.6

Actionable Recommendations for NDIS Advocacy

Based on the research and international precedents, advocacy for an exception to the conflict-of-interest rule should be framed around the following pillars:

Asserting UNDRIP Compliance: Argue that the NDIS Act must be interpreted consistently with UNDRIP Articles 3, 5, and 24. Any decision that ignores the primacy of kinship care is a breach of the right to self-determination and the maintenance of cultural institutions.7

Documenting Market Failure: In areas with no culturally safe providers, advocates must demand that the NDIA fulfill its "reasonable and necessary" obligation by funding the only available support: the family.1

Leveraging the First Nations Strategy: Use the NDIA’s own First Nations Strategy 2025-2030 to hold the agency accountable to its commitments of "community-centred" and "culturally safe" support.49

Challenging the "Informal Support" Myth: Dispute the assumption that Indigenous families have an "unlimited" capacity for unpaid labour. Highlight that in contexts of systemic poverty, "informal support" is a luxury that families cannot afford without sacrificing their own health and economic security.1

A Mandate for Structural Change

The data around the rights of Indigenous Australians reveals a profound disconnect between the aspirational language of the NDIS and the bureaucratic reality of its implementation.

The "conflict of interest" rule, while well-intentioned in a commercial context, acts as a barrier to cultural safety and self-determination when applied to Indigenous kinship networks.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples provides the necessary framework to challenge this status quo. Combined with the successes of the Whānau Ora model in New Zealand and the "substantive equality" victories in Canada, the path forward is clear:

The NDIS must move beyond viewing family members as a "risk" and instead recognize them as the most effective, culturally safe, and sustainable providers of disability support.

The "cultural reasons" exception must be broadened from a rare, grudgingly granted concession to a standard operating procedure for First Nations participants.

This shift is not only supported by international law and national agreements like Closing the Gap but is essential for the NDIS to fulfill its promise of an inclusive and equitable Australia.

By funding the kinship structures that have always cared for Indigenous people, the NDIS can transition from a colonial institution of "structural neglect" into a genuine partner in Indigenous well-being and self-determination.

While we live in hope – hope is not enough for our current clients who are stuck in the colonial wheels of a mechanistic system that disempowers their voice, denies their cultural wisdom, and prevents them from exercising fundamental human rights to choice and control informed by their cultural and undisputed historical sovereignty.

For families dealing with crisis now, today, the NDIS presents an administrative system that even within escalated complex cases under senior planners continues to deny funding even when clinical needs are argued by medical and specialist expert analysis and under reasonable and necessary criteria.

This paper reflects on the discomforting nature of the NDIA as a broken institution that practices inequitable delivery of funding and demonstrates numerous biases and prejudicial policies and practices. These issues very much require attention and reform. But more so, current NDIS participants who are Indigenous Australians deserve so much better.

Action to address Indigenous NDIS participant’s needs must happen now – not in future years or under some future reform agenda.

Works cited

1. Improving Disability Services for Aboriginal People in the Northern Territory | AMSANT, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.amsant.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Improving-Disability-Services-for-Aboriginal-People-in-the-Northern-Territory.pdf

2. Full article: Indigenous experiences and underutilisation of disability support services in Australia: a qualitative meta-synthesis - Taylor & Francis Online, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09638288.2023.2194681

3. The NDIS Workforce and First Nations People, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.ndisreview.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-11/FPDN_Workforce_Paper.pdf

4. Final Report - Volume 9, First Nations people with disability, accessed December 18, 2025, https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/final-report-volume-9-first-nations-people-disability

5. Has anyone had family approved as paid support due to culture? : r/NDIS - Reddit, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/NDIS/comments/1jmhf3h/has_anyone_had_family_approved_as_paid_support/

6. Informal Supports - Peer Connect, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.peerconnect.org.au/oldsite/index.php/download_file/544/534/

7. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and In Plain Sight - Gov.bc.ca, accessed December 18, 2025, https://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/613/2021/03/UNDRIP-and-IPS-FINAL.pdf

8. UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples | OHCHR, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.ohchr.org/en/indigenous-peoples/un-declaration-rights-indigenous-peoples

9. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.un.org/development/desa/Indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf

10. TRANSFORMING DISABILITY ACCESS for Indigenous Australians, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.iuih.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/IUIH-Submission-Disability-Royal-Commission.pdf

11. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

12. Support coordinators and conflict of interest | NDIS, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.ndis.gov.au/providers/working-provider/support-coordinators/support-coordinators-and-conflict-interest

13. Conflicts of interest in the NDIS provider market, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.ndis.gov.au/providers/provider-compliance/conflicts-interest-ndis-provider-market

14. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples - ohchr, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/IPeoples/UNDRIPManualForNHRIs.pdf

15. Empowering the Unpaid Carer in the NDIS Framework - Special Voices, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.specialvoices.com.au/empowering-the-unpaid-carer-in-the-ndis-framework/

16. Including Specific Types of Supports in Plans - NDIS, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.ndis.gov.au/media/8008/download?attachment

17. Can I Be My Child's NDIS Support Worker? - 24seven Plan Management, accessed December 18, 2025, https://24sevenplanmanagement.com.au/am-i-allowed-to-be-my-childs-support-worker/

18. What are conflicts of interest? (DOCX 54.9KB) - NDIS, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.ndis.gov.au/media/7392/download?attachment

19. OG - Reasonable and Necessary Supports | PDF | Caregiver | Disability - Scribd, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/910151450/OG-Reasonable-and-Necessary-Supports

20. Your burning questions answered - My Plan Manager, accessed December 18, 2025, https://myplanmanager.com.au/burning-ndis-questions-answered/

21. Reasonable and Necessary Supports | NDIS, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.ndis.gov.au/media/7772/download?attachment

22. Download Delivering Parent Pathways Guidelines – Part B - Department of Employment and Workplace Relations, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.dewr.gov.au/download/16588/delivering-parent-pathways-guidelines-part-b-operational-guidance/41183/delivering-parent-pathways-guidelines-part-b-operational-guidance/docx

23. We contest the NDIA's justification for NDIS independent assessments - People with Disability Australia, accessed December 18, 2025, https://pwd.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/SUPP-SUB-08042021_JSC-Critique-of-NDIA-Independent-Assessment-Submission.._.pdf

24. The lack of NDIS services for First Nations people with disability 'a national crisis', accessed December 18, 2025, https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/news-and-media/media-releases/lack-ndis-services-first-nations-people-disability-national-crisis

25. Whānau Ora | RANZCP, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.ranzcp.org/clinical-guidelines-publications/clinical-guidelines-publications-library/whanau-ora

26. The Whānau Ora Outcomes Framework - Te Puni Kōkiri - Ministry of Māori Development, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.tpk.govt.nz/docs/tpk-wo-outcomesframework-aug2016.pdf

27. Government restores fairness for family carers | Beehive.govt.nz, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/government-restores-fairness-family-carers

28. Government to deliver family carers $2000 pay rise, expand scheme to spouses this year, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/government-deliver-family-carers-2000-pay-rise-expand-scheme-spouses-year

29. FAQ | First Nations Child and Family Services and Jordan's Principle Settlement, accessed December 18, 2025, https://fnchildclaims.ca/resources-support/faq/

30. Without denial, delay, or disruption: - Canadian Child Welfare Research Portal, accessed December 18, 2025, https://cwrp.ca/sites/default/files/publications/jpreport_final_en.pdf

31. Reformed Approach to Child and Family Services, accessed December 18, 2025, https://fncaringsociety.com/sites/default/files/2024-03/38504%20Reformed%20Approach%20to%20CFS%20v7f.pdf

32. Timeline: Jordan's Principle and First Nations child and family services, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1500661556435/1533316366163

33. Celebrating Five Years of Indigenous-led Child and Family Services Law - Canada.ca, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-services-canada/news/2025/01/celebrating-five-years-of-indigenous-led-child-and-family-services-law.html

34. Annual Report to Parliament 2024 - Indigenous Services Canada, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1728913460798/1728913482672

35. National Agreement on Closing the Gap | Communities and Justice - NSW Government, accessed December 18, 2025, https://dcj.nsw.gov.au/content/dcj/dcj-website/dcj/community-inclusion/improving-aboriginal-outcomes/national-agreement.html

36. Closing the Gap | NIAA - National Indigenous Australians Agency, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.niaa.gov.au/our-work/closing-gap

37. The National Agreement on Closing the Gap - Coalition of Peaks, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.coalitionofpeaks.org.au/national-agreement-on-closing-the-gap

38. Closing the Gap - Australian Government Department of Social Services, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.dss.gov.au/closing-gap

39. Closing the Gap - Parliament of Australia, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_departments/Parliamentary_Library/Research/Briefing_Book/47th_Parliament/ClosingTheGap

40. Summary and Overview: - Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect, and Exploitation of people with Disability Final Report - Mental Health Coordinating Council, accessed December 18, 2025, https://mhcc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/MHCC_Summary_-Overview_-Disability-Royal-Commission-4F-7.11.2023.pdf

41. Human Rights Law in Queensland, accessed December 18, 2025, https://queenslandlawhandbook.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/64.-human-rights-law-in-queensland-december-2020.pdf

42. Human Rights Act 2019 - Queensland Legislation, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/whole/html/current/act-2019-005

43. Human rights | Your rights, crime and the law - Queensland Government, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.qld.gov.au/law/your-rights/human-rights

44. Human Rights of People with Disability - Queensland Law Handbook, accessed December 18, 2025, https://queenslandlawhandbook.org.au/the-queensland-law-handbook/health-and-wellbeing/disability-and-the-law/human-rights-of-people-with-a-disability/

45. Strengthening Queensland's human rights act, accessed December 18, 2025, https://brq.org.au/strengthening-queenslands-human-rights-act/

46. National Disability Insurance Scheme | Administrative Review Tribunal, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.art.gov.au/applying-review/national-disability-insurance-scheme

47. Chapter 10 – Parliament of Australia, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/National_Disability_Insurance_Scheme/NDISPlanning/Final_Report/section?id=committees%2Freportjnt%2F024487%2F73192

48. Tennant Creek boy with cerebral palsy placed in care after NDIA pulls funding | National disability insurance scheme | The Guardian, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/jul/11/tennant-creek-boy-with-cerebral-palsy-placed-in-care-after-ndia-pulls-funding

49. First Nations Strategy | NDIS, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.ndis.gov.au/strategies/first-nations-strategy

Disclaimer

The content provided in this article is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, clinical, or specialist behaviour support advice. It should not be relied upon as such.

All information is provided in good faith, however, we make no representation or warranty of any kind, express or implied, regarding the accuracy, adequacy, validity, reliability, or completeness of any information. The information pertaining to NDIS and related issues must be individually determined by each person’s circumstances and their specialist therapist teams, and is a very complex evolving context and support needs and methods are subject to change.

This article is not a substitute for professional advice from your qualified GP or specialist for from your NDIS Behaviour Support Practitioner. You should always consult with an appropriate professional to address your specific circumstances. Under no circumstance shall Ability Therapy Specialists Pty Ltd have any liability to you for any loss or damage incurred as a result of the use of this information. Reliance on any information provided in this post is solely at your own risk. This article, website, and your participation are governed under the Client Booklet - Privacy Policy: Disclaimer, Terms, Conditions as a necessary provision under Australian service quality standards.